Research Report

The Store of the Future: An Exploration & Planning Guide

The Store of the Future: An Exploration and Planning Guide examines the ways the digital world is blending with the traditional world and emerging technologies are reshaping the shopping experience.

Although the report doesn’t offer one specific path forward, it outlines many ways traditional retailers could employ artificial intelligence, augmented reality, virtual reality and even robotics to enhance the shopper experience. Like all council reports — designed by retailers for use by other retailers — this new study should serve as a catalyst for discussion and action.

One thing is certain: the future is going to look very different than the past. Now is the time for retailers to take a close look at where shopping is headed and talk seriously about how to adapt.

Preface

Introductions

The Coca‑Cola Retailing Research Council

This Store of the Future publication is sponsored by the Coca Cola Retailing Research Council (CCRRC) of North America. The CCRRC was created by The Coca‑Cola Company in 1978 to provide third-party research to its retail customers. Today, the Coca‑Cola Company continues to support the Council to ensure that all grocery and convenience retailers have access to relevant insights that can help them grow their businesses. The CCRRC councils are present on five continents.

CCRRC members identify projects they deem to offer significant value to the entire industry, as well as their own companies. The retailers of the CCRRC determine their own path, including the projects they pursue, and the consultants hired to work on various projects: “Research by Retailers, for Retailers.”

The CCRRC commitment to improve the entire retailing industry is supported by http://www.ccrrc.org/, a website where all completed studies are made available for anyone to read and download. Current members that commissioned and participated in the building of this report:

Rod Antolock

Kroger / Harris Teeter

Steve Junqueiro

Save Mart

Armando Perez

HEB

Mimi Song

Superior Grocers

Peter Whitsett

Meijer

Jonathan Berger

The Consumer Goods Forum

Jay Marshall

Hy-Vee

Leslie Sarasin

FMI

Judy Spires

King’s

David Zallie

Shop Rite

Steve Goddard

Winco

Rich Niemann

Niemann Foods

Garry Senecal

Loblaws

Mike Vail

Delhaize

Michael Sansolo

Research Director

Kantar Consulting

For this project, the CCRRC partnered with Kantar Consulting, a global specialist growth consultancy with over 1,000 analysts, thought leaders, software developers and expert consultants located across developing and mature markets worldwide.

We help our clients develop and execute brand, marketing, retail, sales, and shopper strategies to deliver growth.

We track 1,200 retailers globally, have purchase data on over 200 million shoppers and forecast social, cultural and consumer trends across the world.

Our Retail, Sales & Shopper (RS&S) practice enables clients to sell more effectively and profitably by turning insights into action and shoppers into buyers.

In an ever more complex and competitive environment, Kantar Consulting has relevant strategies, insights and analytics to help clients grow their businesses, backed by our team of experienced consultants and next-generation organizational capabilities.

For more information, visit consulting.kantar.com.

Overview for the Reader

Business leaders worldwide are contending with various aspects of a common dilemma: they can all see the future bearing rapidly down upon them and must adapt quite literally on the fly. But several aspects of the future remain unclear, especially given the speed of changes in technology, media, products, and people. Without knowing the details of what the journey to the future requires, they don’t know “what to pack” to be prepared and competitive. So, more often than not, they are grabbing everything that looks vaguely like it may be useful or that seems to be popular with other, equally threatened competitors.

Other industries, especially the technology and medical sectors, have been buying out and frequently overpaying for hundreds of companies (of all sizes and areas of expertise) for years to prepare for this unknown. In retrospect, these moves to acquire new skills and capabilities often seem to be of questionable value as leaders search for a tool, advantage, or pipeline solution to make them uniquely competitive in the near term and future. A large part of the venture capital rationale for investing is based on this race to find the ‘killer app’, an acceptable risk since the future need is still poorly known.

But the retail sector does not lend itself to such flexibility. The demands of everyday execution in complex retailing organizations means that bolt-on structures, grand acquisitions, or new functionalities of uncertain utility return of investment (ROI) are rarely viable. Key barriers are not just investment levels. Barriers also include balancing near-in time requirements and strategic focus, which are critical for a retailer to stay relevant to the shopper and remain competitive in the marketplace. Unsustainable fads can be even more expensive for corporations than categories, and can distract retailing “energy” from the core mission. Unlike research, retailing changes must take place in the here and now, operational time.

At the same time, defining what the store of the future can and should be provides planning topics to consider in context, helping to guide the inevitable tradeoffs between investment in an ideal vision or solution versus the realities of meeting today’s financial obligations. To that end there is a need to not only address evolving shopper expectations but also to ensure ROI, while still contending with legacy infrastructure, changing needs for employee skills and training, and the accelerating technology shifts. In short, the store of the future needs to be practical in discussion and planning, not merely an abstract vision statement.1

Our research methodology and resulting insights are based on a core belief that, despite the waves of change impacting the retailing industry, physical stores will continue to play a vital role for all parties involved in retail — shoppers, retailers and suppliers.

That role will continue to be enhanced and impacted, and certain functions are clearly undergoing more strain and thus will require more revision than others. Today’s “mass market” (tactical) responses that are untethered to a broader strategic vision won’t carry the day. So our research was designed to imagine the retail ecosystem of 2030, and draw logical conclusions of how the “store” will evolve starting today to adapt to the future state of tomorrow. To that end, we studied what’s developing today, plotted out what’s likely to evolve in the future—grounded in shopper behaviors and retailer capability development—to paint a picture of the store of the future. Our intent is to leverage this research to uncover a viable strategic vision to guide store-focused planning and development in the coming decade.

1 In-store marketing agencies, media planners, and technology providers may also find value in assessing future partnership opportunities highlighted in this study.

Key Findings to Consider

Predicting the future should by design provide some level of surprise, but it’s not an impossible feat. We often lack a clear view of ten years out not because trends are not clear today, but rather because almost everyone who tries to extrapolate the future leans to the side of caution — it’s tough to be bold when projecting what’s likely to evolve, especially when attempting to predict when. Nonetheless, our research has revealed some interesting surprises, largely stemming from how many fundamental retailing elements are undergoing massive change. For example, we’ve learned how vital the tight coordination must be linking store employee training, store management and operations, and the shopper’s digital experience — particularly in fulfillment. With an almost endless array of potential implications from our research, we’ve condensed our key takeaways and planning themes into a reasonable set of elements to guide future action.

The key findings for where the management of the store of the future will need to focus are discussed on the following pages.

Shopper Enablement

Delivering a totally seamless trip will require enabling the “fully integrated” shopper using equally integrated information systems during preshop, transit, and then in-store. The retailer of the future will need to enable shoppers and flawlessly meet their needs as they plan a trip, complete ordering from home or work, even interact while the shopper is in transit. Multiple and flexible fulfillment options will be provided to the shopper in a reliable, flexible, and seamless manner. The retailer of the future cannot and should not attempt to separate the store or the shopper from the digital world.

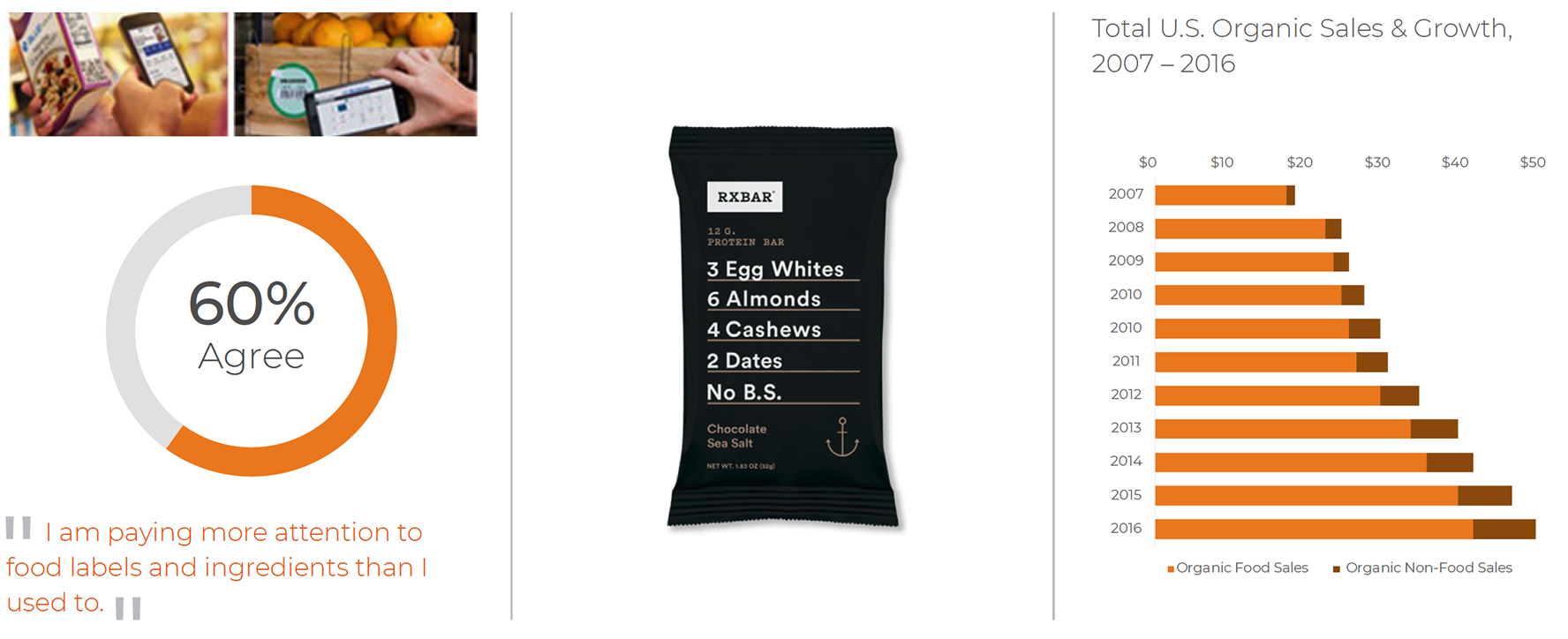

Linking the store to product authenticity, quality sourcing, and food safety — informing and improving product assortment and selection with references to health, wholesomeness and quality, as well as connectivity back to “the farm” — the store must embrace its role of communicating and ensuring quality sourcing and product reliability. Educated, curious, and risk-averse shoppers will want to validate the health benefits of products; be informed of possible recalls or threats in real time; and be assured of a level of wholesomeness, consistency, and ethics on a variable but increasing “scale of judgment.” This relationship must be two-way and interactive — think ratings and reviews — not a one-and-done advertising program. The store of the future must enable the education and informed judgment of shoppers and take a position of being a meaningful advocate and local resource for an increasingly concerned — but also adventurous — community eager to experience new things without risk.

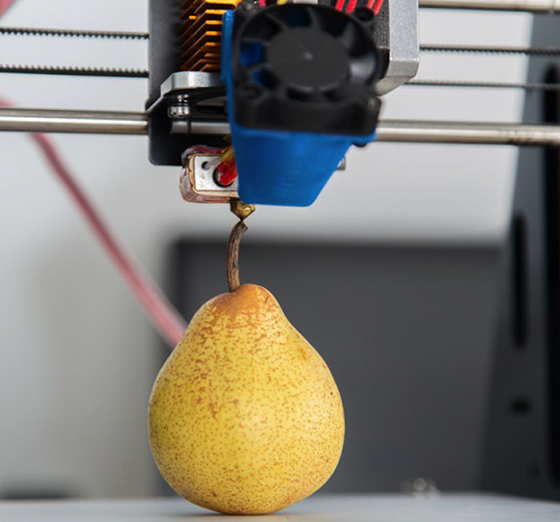

Packaging up the total food solution — whether a single meal solution or a week’s worth of dinners — the store will become a meaningful resource for loyal shoppers. The store of the future will need to communicate effectively, guiding the shopper to relevant rewards, healthy diet choices, and product usage. When the shopper asks, “What’s for dinner next week?” the store of the future needs to answer, incorporating a more complete understanding of the individual shopper, history, preferences, health concerns, and similar purchase decision factors. Moreover, future 3D printing of new food ingredients will open the door to increasingly customized flavors and textures not currently known.

Technology Deployment

Effectively using and expanding the role of Financial Technology (fintech) to shift shoppers’ focus from price sensitivity to value created by a frictionless experience. Shoppers will always care about managing their money, but increasingly they’ll care more about saving time. As more investment brings down the relative cost of things like automatic payment, home delivery, and auto-replenishment, shopper expectations will continue to rise. Offering a good price will always matter — but that will become the cost of entry, rather than the driver of shopper loyalty. Technology will be deployed to readily identify, validate, and assist shoppers throughout the shopper journey into, throughout, and while exiting the store, delivering a frictionless experience.

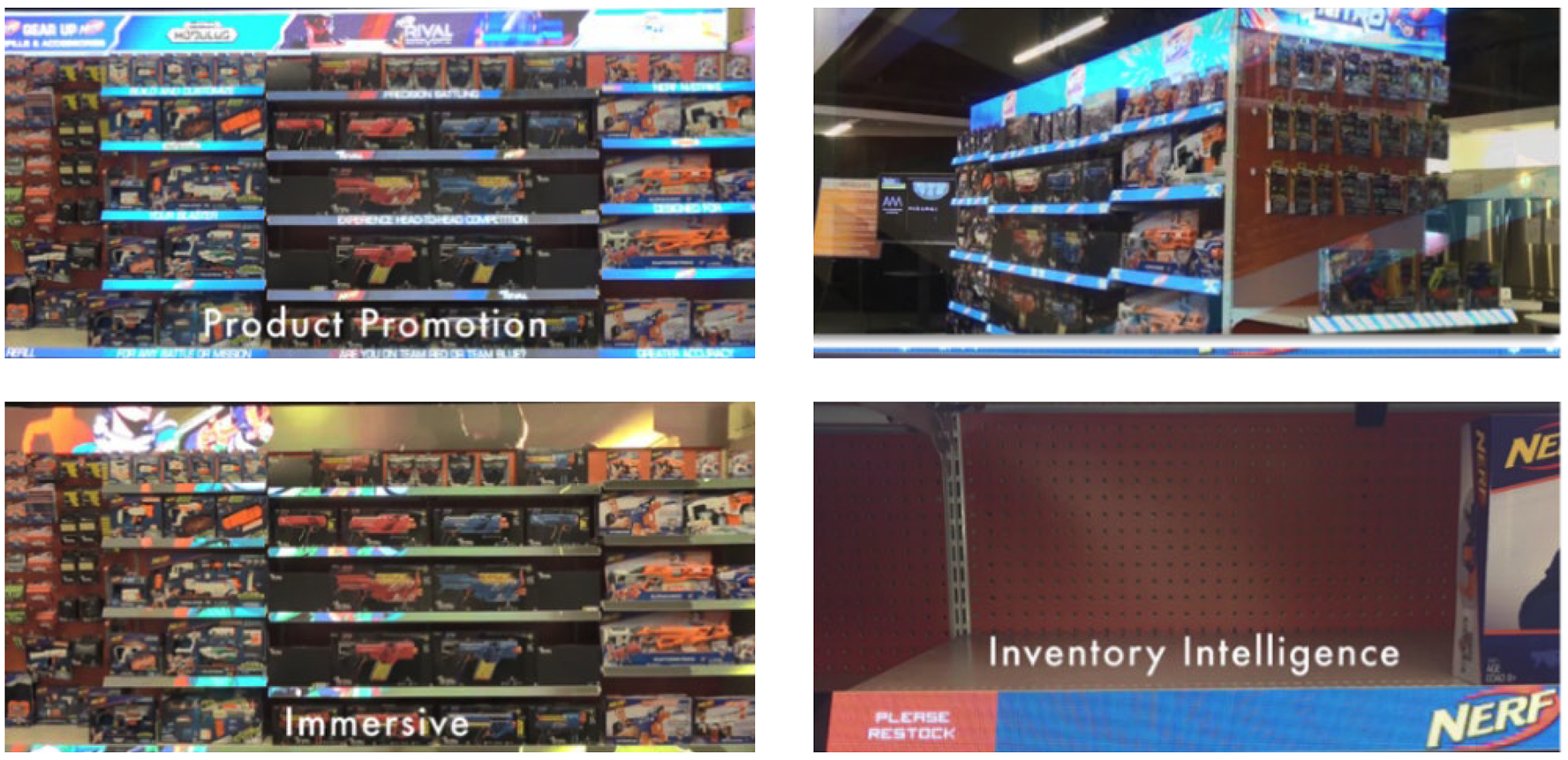

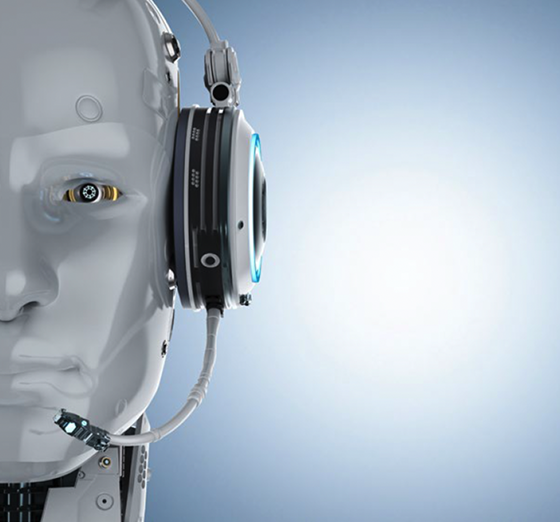

Providing an interactive shopping experience, leveraging digital and augmented reality in the store for both the shopper and the employees. The store of the future will have available a wide range of technology, ranging from heads-up, verbal/audio interfaces for employees, to integrated in-store robotics to improve operations, to interactive information and navigational support for shoppers. Technology will enable a higher level of responsiveness, connecting inventory management, customer service, resource deployment, merchandising, and marketing.

Effectively deploying integrated digital fixtures in the center store will be critical to expand shopper awareness. Flat signs and intrusive shelf talkers must evolve from what they do today. As smartphones increasingly offer active, colorful, and even augmented reality, the store must be enabled to interrupt the flow of competing communications to reach shoppers even while they are in the aisle. This capability should also morph regularly to incorporate evolving media types to help keep the experience fresh, but also reliable as an enhancement of benefits to shoppers as they visit the store over time.

Providing more options and new interfaces to converse with shoppers — sense, respond, and engage further. Merchandising, AI/robotics, and employees will be integrated such that when working with shoppers they can sense shopper needs sooner, respond more creatively, and drive a longer conversation. That in turn creates new metrics for measuring how these work to create a range of outcomes, especially increased total spend and return engagement. The store will be measured in ways related to the success of that conversation over time.

Enabling frictionless transactions to complete the sale, providing for payment security and speed. Face and motion recognition, along with the expanded norms of electronic signatures, offer additional areas of retail technology that will improve transactions, individual identification, and speed of interaction. Proper implementation will enable real-time management, monitoring, and improvement, reducing the friction currently inherent in completing the sale. At the same time, identification and verification layers will help reduce shrink in a range of new ways.

Leveraging Core Assets

Improving the (critical) interdependencies between Employee and Manager — staffing with real people will matter in future retail — but not in the same ways we think about today. With just a few exceptions, most retail staffers are divided into a large pool of replaceable workers — characterized by minimal formal training and separated from key skilled positions by pay scales, experience, and longevity. Retail in the future will have fewer of the former and a lot more of the latter — and they will need significantly more new capabilities and skills than they currently possess. The retail store of the future will allocate more time and investment in training, which will enhance overall job satisfaction and retention rates. New operational processes will be needed. They will incorporate new and better applications throughout the store as they become more sophisticated to cope with complex requests — as the norm rather than the exception during other work flows. Good design will enhance food service, for example, to address both the shopper benefits and experience of in-store fulfillment.

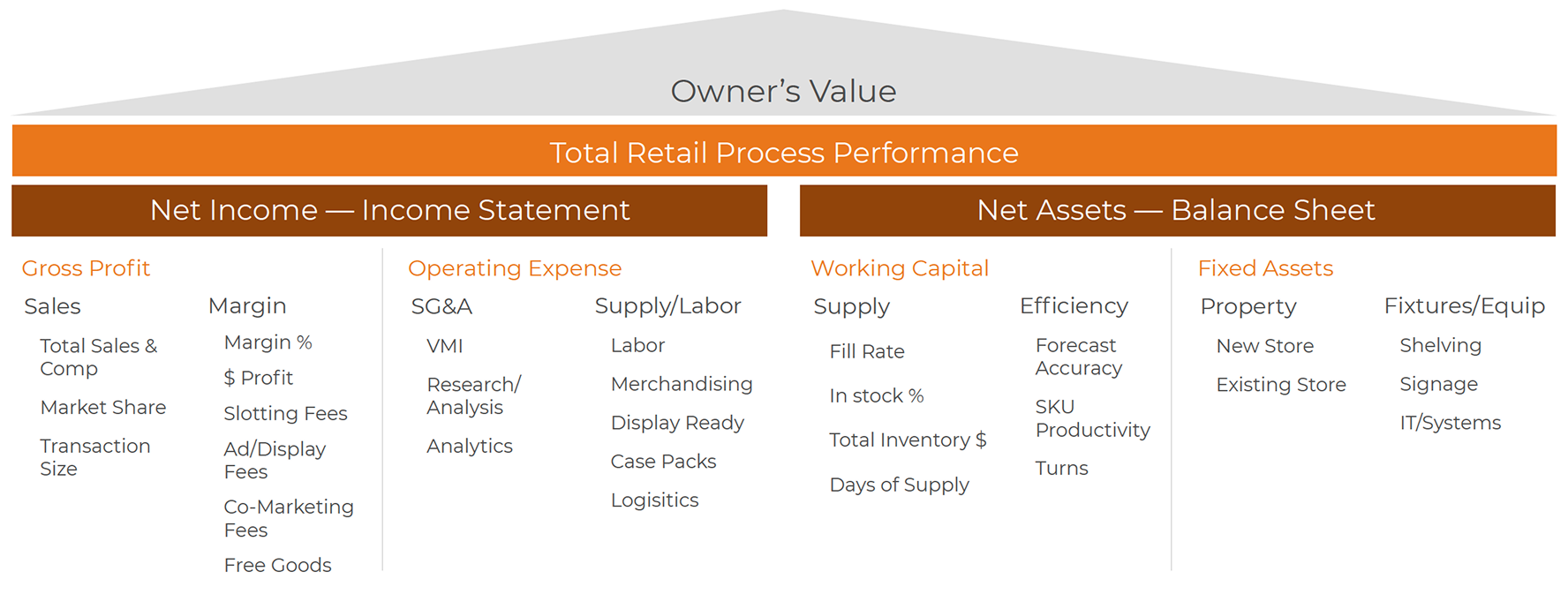

Leveraging the store to guide total business operations, including key performance indicators (KPIs) — financial planning and KPIs will evolve to measure success. Such changes will create the operational store of the future, but will also require new means and metrics for managing and directing the enterprise at all levels. The future business will generate far more data than is the current norm. This will lend itself to more dynamic and more situational KPIs such as collective shopper time engaged with merchandising, successful hand-offs of employees to robots in meeting shopper needs, and the effectiveness of new forms of transactions to reduce liabilities and increase asset turns.

Scenarios of the Future

The future is often easier to describe than to visualize, considering how the extraordinary of today will be considered quite ordinary in just a decade’s time. In the future, stores will still enable interactions between shoppers and employees; however, we must consider different points of view regarding how a “normal day” for each may unfold. The digital and Internet-enabled landscape will be more pervasive than what we experience today, but also more accepted as an integrated background to the store and the shopper. Consider as well how changes in technology, processes, and enablers become quickly accepted as the new normal.

The Shopper in the Store

The shopper of the future will be virtually connected to a range of groups—service organizations, family and home networks, even her key retailer—with full expectation that all of them will integrate seamlessly throughout her day, not as ongoing “interruptions.” Her kitchen appliances add items to her shopping list, her home network monitors inventory and consumption rates. She will likely expect that the store, her phone, and her home network are in constant synchronization. Her purchase history will be transparent, her product preferences known and catered to. Her preferred retailer is aware of her as a unique individual, as a purchase agent for her family, and as a shopper with a series of nested ranges of tastes, needs, and areas of interest.

Our research methodology and resulting insights are based on a core belief that, despite the waves of change impacting the retailing industry, physical stores will continue to play a vital role for all parties involved in retail — shoppers, retailers and suppliers.

As the shopper traverses the store, messaging appears, much of it targeted to her purchase history and expressed product preferences. She has opted out of some, accepted others, and has the choice to ask for more detail at certain stations along the way. Much of this information is seamlessly transmitted to her physically embedded SmartSystem™, which long ago replaced many of the functions of her external phone. Because the SmartSystem is part of her physical body, it allows her to hear content without the use of speakers or earbuds. Other shoppers wandering around the store are using older, handheld systems, but she is an early adopter.

Her list is shorter than it used to be—a good deal of her regular replenishment purchasing was completed and delivered to her home several days ago, as it is every week. Although the center of the store still exists, it is much smaller than it used to be—much of the former inventory now transships directly to her home without spending time on the store shelf. She doesn’t really notice several of the changes, or care why—but she does recognize that it is much easier to walk the store and find her favorite items than it used to be. With the bulk of replenishment items now delivered automatically, the trip to the store takes much less time.

Less rushed, she has a few more minutes to browse and is pleasantly surprised at several new product offers—in most cases the information systems built into fixtures of the store allow her to examine products in detail if she desires. This functionality offers helpful information related to ingredients, nutritional information, origins and sourcing, along with peer reviews of the product and the price. From time to time her queries connect her to centralized store information systems run by a limited but effectively programmed artificial intelligence (AI) “agent” who manages a brief conversation with her. This interchange is routine, and now expected. The store is ever changing, presenting new products and bringing other helpful options to her attention. Over the course of several trips, she is usually exposed to something new, whether a product, a service, or some combination of the two. Sometimes she buys them, sometimes she adds them to her home-delivery list, and at least one thing, though interesting, she tags for future consideration. It is not clear whether this tag remains on her own personal system or is managed by the store. She doesn’t care. Her facial and emotional reactions to new offerings are noted and collected as part of the store monitoring process—that live response data is valuable to the store.

At the bakery, she discloses a custom request, a birthday cake for her youngest, a toddler. A higher level AI intercepts and prioritizes her request, queues it to the human staff, and engages customer service. A record in this shopper’s file notes the occasion and the date of the toddler’s birthday (and age) for future reference and places it in the store’s memory. She will receive a relevant prompt next year, along with existing special dates already registered—her anniversary and several observed holidays.

In the produce department she makes some choices based on bulk price, others on seasonal availability, and some based on origin information. She is fond of local and regionally harvested products. At one point, still unsure, she asks a manager about the ripeness of a melon and they have a pleasant conversation about how to choose based on freshness. The manager calls her by name, as the store recognized her, and the system prompted the manager through a heads-up display to approach her. Though she could have asked the produce robot for advice, the shopper prefers to talk to a live person when in the department. In the wine department, however, she prefers interacting with the wine-bot. She relies on it for recommendations, and it doesn’t make her feel ignorant. The wine robot also amuses her because it is decorated to look like an old-fashioned butler.

The robot also asks if she is pleased with the custom cake that she just ordered and engages in a very human-style conversation about her preparations for the toddler’s upcoming birthday celebration. Both answers are tabulated to the store AI—one for assessment of customer service and the other for potential sales and marketing opportunities. She hardly notices—she is accustomed to the various elements of the store cooperating in a seamless way. To her, the entire store is like a very helpful concierge service, a well-organized personal assistant.

As she moves through the store, selecting products, her choices are tabulated as they enter the basket. When finished, she is charged automatically and seamlessly. There still are cash registers near the exits—but she rarely uses them. Behind her, unnoticed, robots stock shelves, unload trucks, scan shelves, and reorder products. If it were late in the evening the robots would be more obvious, but it’s afternoon, so robots are scarce on the floor. The cleaning and maintenance robots only emerge at night.

As she drives home, she recalls something she forgot to purchase, but since it isn’t urgent, she simply tells the car, which will pass it along to the house, where it will be added to her next order. After all, she has more important things to think about.

A Vision of the Retailer's Future

The store manager is walking the floor, examining the status of perishables by checking her device to measure the various gas levels and air quality variations that could signal issues. Measurements reveal that melons are in the right state to be sold, but the potatoes are getting close to turning bad. Making a digital-voice note to the department lead, she then repeats the monitoring process for chill cases, monitoring for uneven cooling, leakage from cases, and deli hygiene at the back counter to verify cleaning process adherence. While moving to the in-store restaurant food service area, she is notified by her earpiece of a shopper who has been studying the melons for longer than expected. She quickly diverts to help the shopper find that elusive ‘perfect’ melon while being quietly prompted to ask after the shopper’s family. She makes a comment to the shopper, prompting the wine-bot to check in with the shopper as well. She also notes that the shopper mentioned the wine-bot’s butler costume was amusing and leaves herself a note to explore the idea of putting other costumes on other shopper-facing robots during the upcoming holidays. It might add some fun to the store.

In the store of the future, the manager will still be analytical and decisive, managing a complex environment, but her responsibilities will stretch across the company, the store, and any shoppers seeking assistance.

Lately, the food service area has been a concern, mainly due to the turnover of labor and issues with the automated systems involved in prepping core menu items. The systems are creating a quality sandwich and the wrap is fine, but the timing of production is not matching to spikes in demand at lunch. Investigating a bit, the manager finds that the point of sale is reporting back the information 30 minutes off the purchase — this can be corrected via a small verbal adjustment to reconcile. Another challenge has been the inclusion of the 3-D printer for production of unique food items such as the new meat substitute meal pockets in a lentil-based bread wrap. Though the machine is working to spec, the seasoning recipe defaults to a basic condiment — yet the optional one is being ordered more often. The manager sets up a quick call to review a video of the issue with her chain office and the printer’s manufacturer — the manufacturer can provide a software patch to correct the problem immediately.

The exterior parking lot monitors the arrival of a key loyal shopper, and the manager moves back to the front door to greet her by name; while walking across the store, the manager polls the system to check on the labor costs, sales, and gross margins for the food service area. As expected, the issue with preparation has depressed margins, and the uneven nature of the new labor is impacting productivity. Moreover, further data analysis notes key concerns with the center store surrounding the food solution — overall sales in related categories are softer than expected. Seeing that her actions appear to be addressing the issues, she makes a management note to review the situation again just after the lunchtime rush the next day.

Checking on external orders being made by shoppers for pick-up and for home delivery requests from one of the smart home services, she is reassured that all is running at historic levels. She has also received a request from a supplier that monitors the health of subscribers to promote more meal supplements. The manager reviews the options against sell-through and accepts a few suggestions from the AI system. She comments internally to her procurement group to review the additional requests against existing program metrics. Overall, the performance of center store into the fulfillment of pick-up is exceeding expectations, and she chooses not to adjust the automated inventory ordering.

The Shopper

The Rise of the Epicurean

Today and in the future, shoppers are becoming increasingly selective in their approach to shopping. This balancing of time, energy, and money against “shopper returns” simply means shoppers are savvy. They want to satisfy themselves through good experiences, both in acquiring and consuming good food, but with more emphasis on how all of that aligns well to a lifestyle. The shopper has become empowered in a number of ways, making better decisions and informed tradeoffs via new product information, expanded services, and cost-cutting through reliance on retailer ‘own label’ items. The shopper’s behavior reflects the fragmentation of needs and desires balanced by the constraints of time and money. All of this tradeoff and curation behavior has been enabled via new channels of social media learning and peer-to-peer reviews and interactive communications.

In short, the modern shopper has become an “Epicurean philosopher” of sorts, dedicated to the positive results of seeking pleasure while also honing in on simplicity. The store today and in a decade’s time will need to reflect this duality — in effect, serving an endless supply of “wish list” items while simplifying the entire shopping experience.

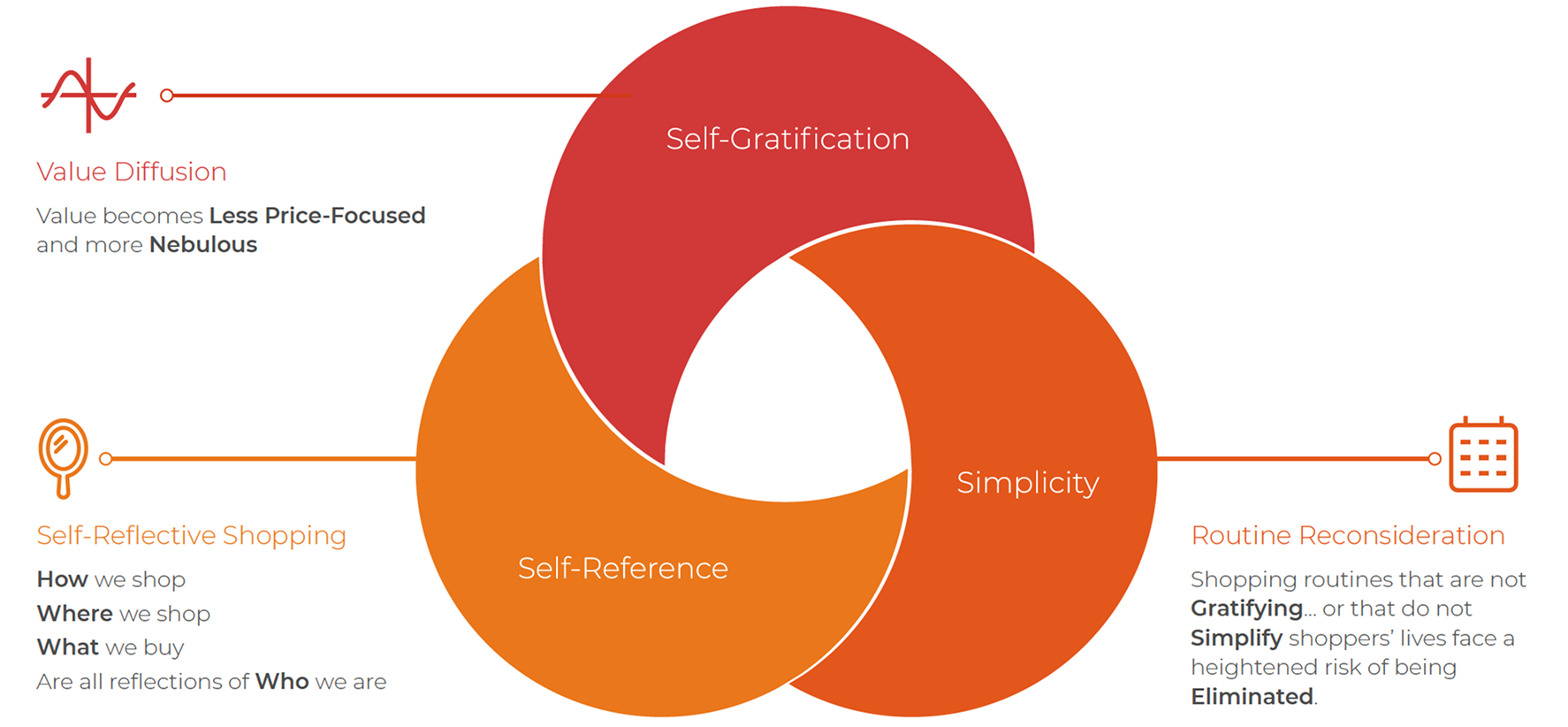

The emergence of the Epicurean Shopper is a result of his or her ability to make choices based on self-gratification and simplicity. eCommerce, along with affordable luxury, has created the means of enabling both.

Future shoppers — across all age cohorts and economic circumstances — will be less likely to accept routine or mundane products and standardized services. Instead, they’ll seek out products and services that are personally resonant and targeted. They will also be impatient with irrelevant advertising messages or navigating options of no personal interest or value.

For Epicureans, self-gratification (What do I want?) is the motive that informs key decisions about where, when, and how to shop; simplicity (Is this experience easy or fun?) is equally key, but simplicity is defined by the eye of the beholder. Self-reference becomes the “normal process” of fitting new selections into the overall lifestyle and supporting routines.

The Epicurean mindset shapes the future shopper by bringing to decision-making self-gratification, self-reference, and simplicity. Retailers will need to address the concerns to the left to reframe their value to shoppers in the future.

Source: Kantar Consulting

2 "A philosophy advanced by Epicurus in 307BCE that considered happiness, or the avoidance of pain and emotional disturbance, to be the highest good and that advocated the pursuit of pleasures that can be enjoyed in moderation.” Source: American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. Copyright © 2016 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Co.

The emergence of the Epicurean Shopper is a result of his or her ability to make choices based on self-gratification and simplicity. eCommerce, along with affordable luxury, has created the means of enabling both.

The emergence of the Epicurean shopper is changing the definition of Value from a simple price message to something more nuanced and complex. Routine shopping is not gratifying, and increasingly it will be eliminated or automated. Therefore, a shopping environment that is entirely predictable is one that is at risk, putting future shoppers at odds with most of the operational certainties that make a traditional store more efficient and thus profitable.

Plan for an emerging gap between shopper expectations of simply finding and buying items (replenishment purchasing) versus shopping — the latter will be increasingly experiential, providing an element of inspiration and discovery.

The separation of replenishment (needs) and discovery (wants) will be driven by technology and the free-flow of information along with fulfillment options. eCommerce has also allowed individual “upstart” brands to interrupt, often disrupt, the purchase process with offers that create frictionless purchasing for something new and interesting, bypassing much of the logistical costs of gaining distribution.

With eCommerce, products can be bundled into groups, reflective of individual preferences, and responsive to demonstrated purchase behavior at the shopper level. For example, Stitch Fix, Chosen Foods, and NatureBox come to mind — as do private label and retailer ‘own label’ expansions into new categories. The rise of brands provided by Aldi and Lidl in the US market show the future direction of own label development into more Epicurean themes, running parallel with retailers’ need to constantly renew the offer and refresh the shopping experience.

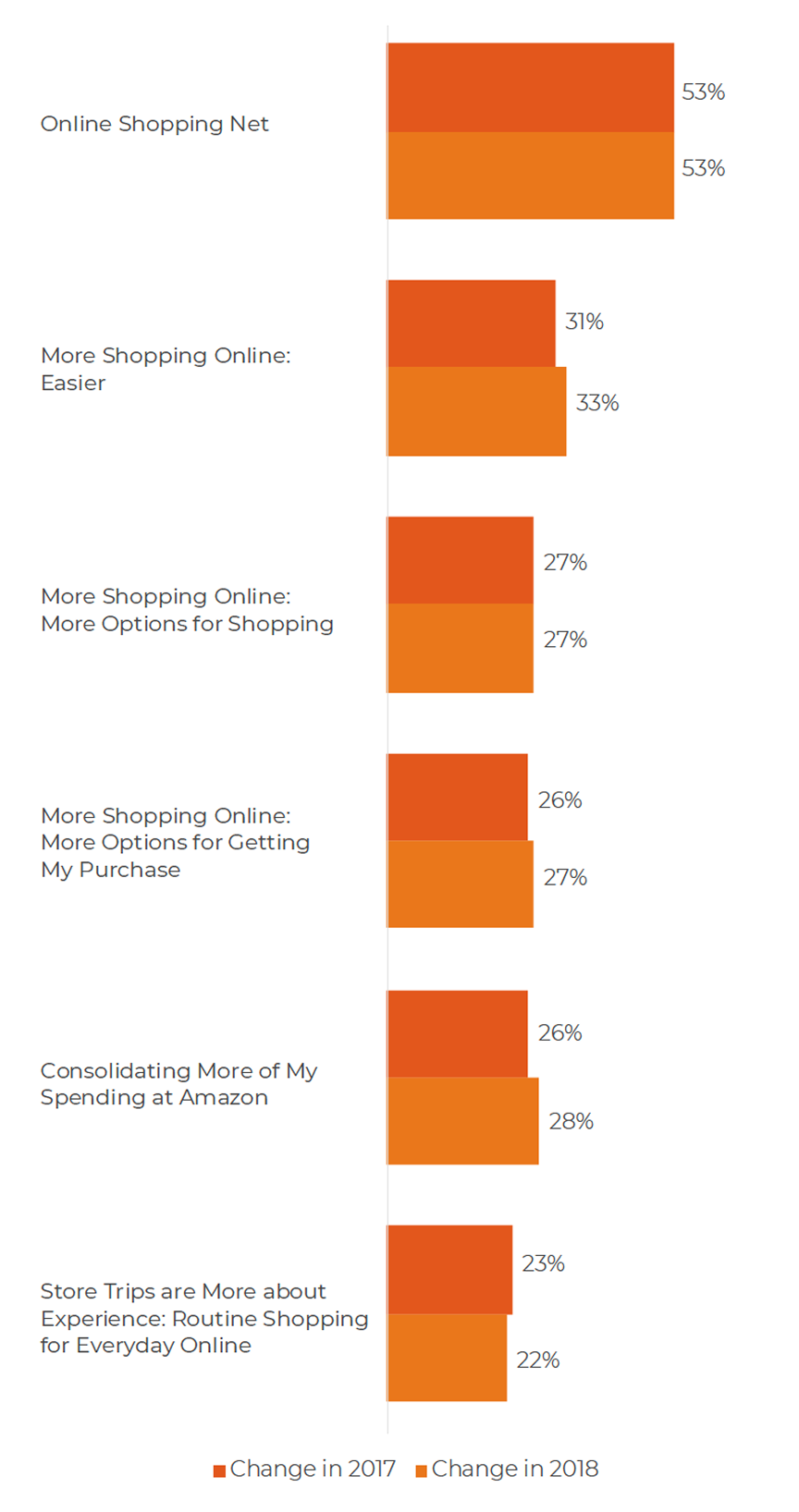

Changes to Shopping Behavior Involving Online Shopping (among all primary household shoppers)

ShopperScape®³ data demonstrates that more than half of all shoppers, regardless of age or other circumstances, are now purchasing at least some of their consumer goods online while lowering their stated needs related to ‘routine’ shopping.

Source: Kantar Consulting.

3 ShopperScape is Kantar Consulting’s proprietary online survey of more than 4,000 primary household shoppers each month. Covering 200+ retail banners, this comprehensive survey provides timely data on retailers shopped, products purchased, spending outlook and shopper attitudes. For more information, go to https://www.kantarretailiq.com/shopperinsights/shopperinsightshome.aspx

Today, cohorts in which this dynamic is increasing are those initially hesitant—e.g., older shoppers, households without children, and less affluent “have not” shoppers. ShopperScape data analysis shows increased adoption of online purchasing across many product categories, and is expanding into travel, banking, and telecommunications—suggesting that online purchasing is now an absolute requirement.

In parallel, note that some things remain true no matter how much changes around us: a store near home is still more accessible than one farther away. A store that contains most of what a shopper wants to purchase is far more convenient than making multiple trips to multiple stores. A clean store featuring clear signage that makes it easy to navigate is more attractive than one without such guidance. Even here, changes in traditional retail are already emerging, mostly defined by evolving shopper preferences.

Fragmentation, referenced earlier as a driver of the Epicurean shopper, is the growing challenge for retailers. Fragmentation manifests in the store in nearly limitless individual taste preferences, fueled by bifurcation in incomes, age cohort attitudes, and increasingly diverse cuisine preferences. The shopper landscape today is dynamic and wildly variable—often at odds with traditional (homogenous) consumer blocks viewed as the “consumer target” or “core shopper.” The notion of monolithic targets, averages, and predictable behaviors is not only inaccurate, it inevitably marginalizes the products or retailing offer based on the narrowing or filtering process. For legacy retail formats, outdated methods of targeting “mass consumers” pose both a physical and virtual challenge of adapting the shopping space to a more selective, individualized shopper base that does not lend itself to mass marketing and chain-wide merchandising.

Shopper fragmentation may be the most challenging of trends, simply because it cuts against the existing metrics of efficiency for most retailers and suppliers of fast moving consumer goods (FMCG), including supermarkets and mass merchants with competitive offers. For nearly a century, the grocery store has been designed to appeal to the greatest number of people, attempting to satisfy all sorts of trips, tastes, and preferences for all possible shopper cohorts within the trade area, well supported by brands of national focus with broad acceptance.

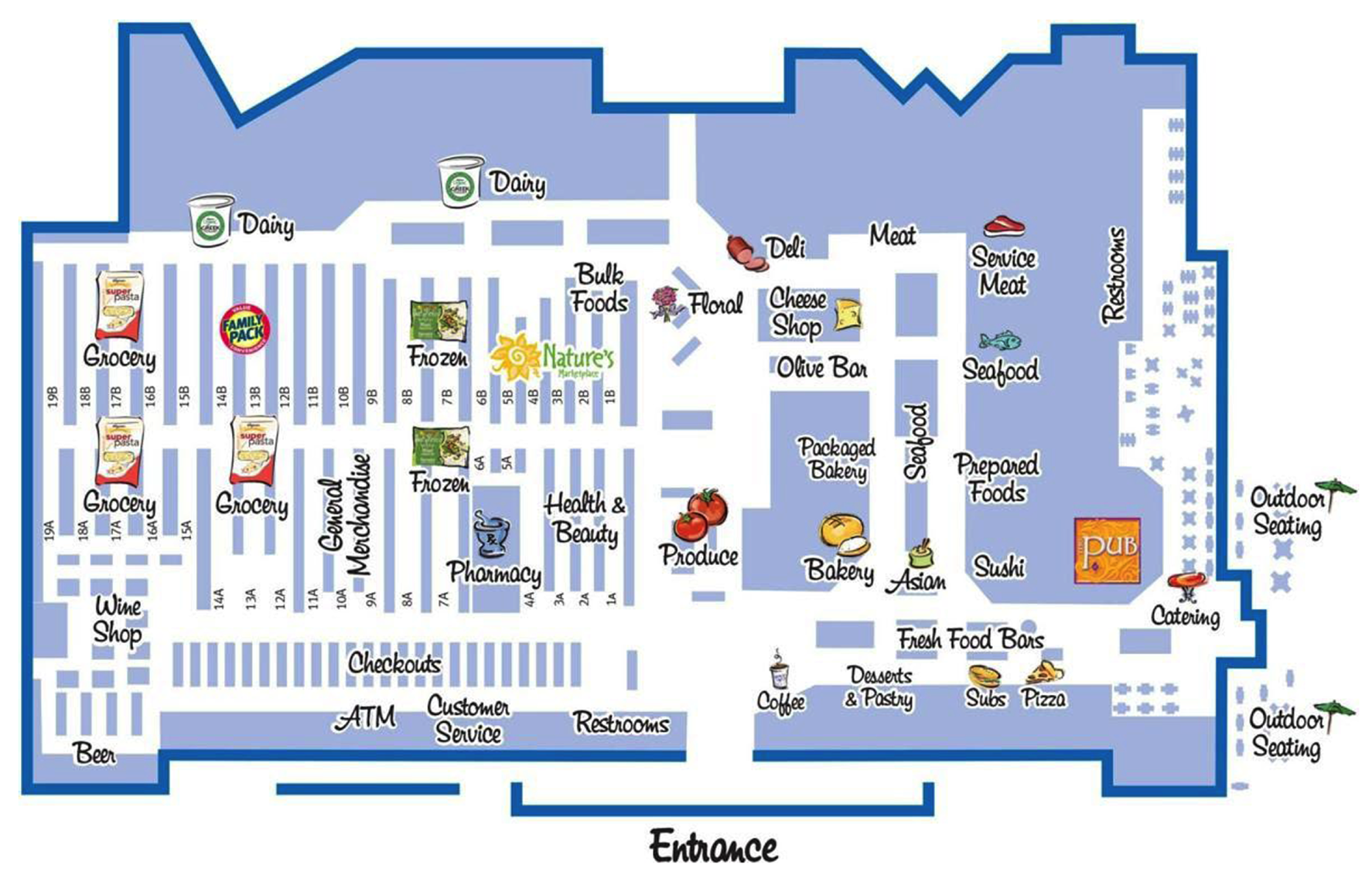

Wegman’s Roanoke, VA store map shows the high-end experience food court, perishables, and food solutions of the store on the right separated from the price-sensitive and lower experiential ‘center store’ to the left. The combination captures a wider range of shoppers. Source: Wegman’s via Roanoke Times (November 2016).

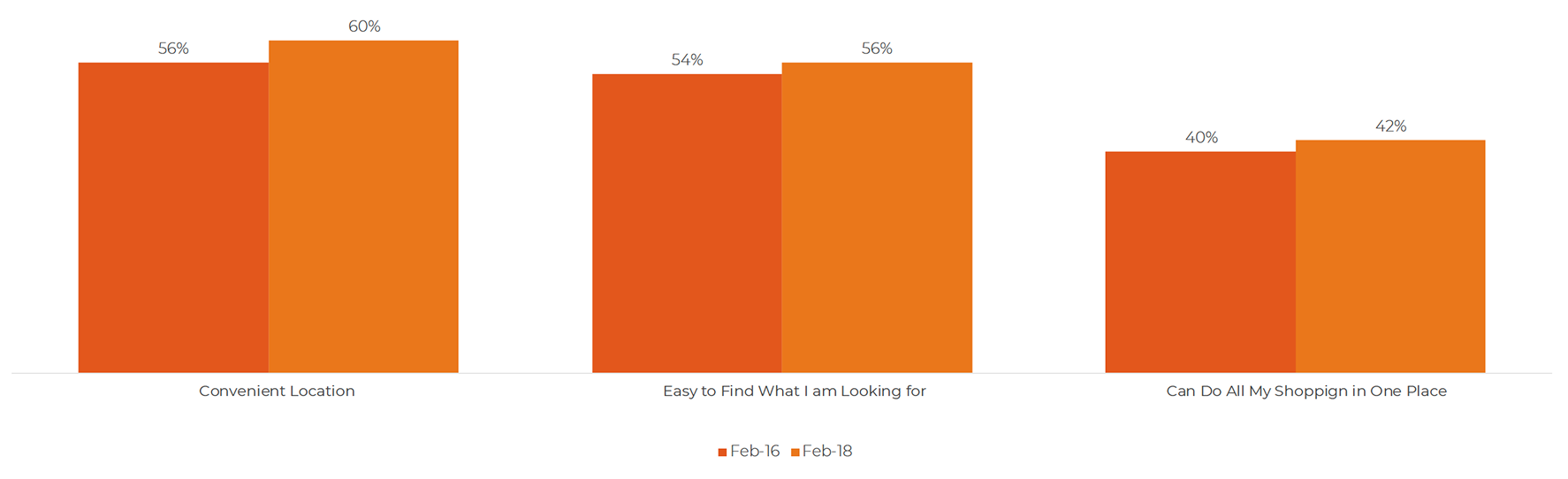

Shoppers Who Rate Factor as "Extremely Important" When Shopping for Groceries

Note: Arrows indicate statisitically significant year-to-year difference (95% Confidence Level). ShopperScape© data shows a consistent shift upward over concerns related to friction and time — including the convenience of the location (which increasingly is online as well as in-store), ease of finding desired products, and the ability to complete shopping in one place and time. Source: Kantar Consulting

One solution to fragmentation was the hybrid grocery store, depicted in the Wegman’s format on the prior page. This format provides for enhanced shopper experiences (mostly tied to the perimeter) along with a cost-sensitive center-store environment. Wegman’s and Loblaws provide strong examples of this approach. In the future, we expect the “cost-sensitive space” of center store to shift progressively (for the shopper) over to a growing number of online replenishment options. The business challenge remains: Can the retailer capture those shifting sales within its own omnichannel operations? The reward and risk are significant in capturing replenishment sales while preventing leakage from other departments.

The Hybrid Store solution will continue, but with the virtual focused on replenishment while the center store becomes increasingly focused on an improved experience.

Shoppers today are clearly showing the way to the future they want. They are empowered and determined to compare items, relevant reviews, pricing, features, and availability using technology that will quickly shift from handheld devices to more pervasive access. Those same shoppers are already in “conversation” with marketing messages about stores, products, and categories that are almost wholly independent of the supplier and retailer role. Individual contributors to blogs and in-site comments, third-party review organizations along with greatly enhanced soft information (e.g., industry or consumer rumors) may well be based on opinions and not usage, much less purchase. Retailers attempting to use this greater sphere of marketing-message influencers do so today with caution; yet, in the future, it may be the only effective means of marketing to an information-driven shopper.

The commonality across all shoppers is to avoid friction such as that caused by fruitless searches, finding information when desired, affordability of selections, safety concerns, and payments. All retailers today and in the future are concerned with these factors but need the ability to create some friction (or slowing) to get the customer to consider new products, be influenced by merchandising, and marketing—regardless of being online, in-store, or in various combinations. In the future, shoppers will expect consistent messaging and frictionless purchasing across any routes of shopping; all the while, retailers will be learning from the endless data streams available to eliminate friction or the number of interruptions to make for a more profitable shopping trip.

The Shopper in the Center Store

The shopper continues to show a marked and growing preference for the perimeter, and far less interest in the center of the store. In 2011, 49% of shoppers reported using the center store and perimeter equally; by 2018 that has dropped to 40%. Nearly 4 of every 10 shoppers to conventional grocery stores today shop the perimeter exclusively. This has enormous implications, not just for store design, but for the operating business model of the store. In the current state, the seemingly endless proliferation of items available across categories has crowded the space and made item selection difficult, sometimes beyond the capacity of most shoppers to navigate.

While producing enormous financial incentives for retailers, having endless choice and full aisles of comparable products are no longer a positive aspect for shoppers overall. This strategy also creates an operational burden for inventory. While category managers work within each section to authorize and stock the most popular items, this creates the effect of “sameness” across all stores in the same area. The other problem is that unique items struggle to be noticed, unless they’re heavily supported at launch.

Just as retailers must contend with a more complex marketing environment, many manufacturers also struggle to compete for consumer attention in a world of new media channels and modes. They struggle to find growth in this “information overload” environment. Many supplier companies default to what they know how to do best: line extensions and packaging variations. These are low risk but do little to generate absolute growth or new shopper trips to retail.

% of Shoppers Who Shop Perimeter Departments and Center Store Equally

% of Shoppers Who Go up and down Every/Almost Every Center Store Aisle

37% of Shoppers Primarily & Exclusively Shop the Perimeter

ShopperScape data shows the shift of shoppers not only to the perimeter but as the primary area of solutions being sought.

Source: Kantar Consulting

Aldi (top) and Lidl (bottom) present an upscale store experience and innovative own label products with discount pricing. Source: Kantar Consulting Store Tours

The Future Store will not be limited to physical and virtual space; it will also express value more dynamically via retailer ‘own label’ offerings.

Contrast this with Trader Joe’s, the Aldi-owned chain that has invested heavily in creating a brand that is deliberately quirky, based on limited inventory and regular product rotation, and majority private label. Many Trader Joe’s stores are deliberately laid out to surprise shoppers, with angled aisles that allow for meandering and discovery. Virtually every store has sampling stations with knowledgeable employees. The staff is very well trained, mostly full-time, and highly interactive with shoppers, even at checkout. Marketing and advertising are the retailer’s responsibility, executed for the store-as-a-brand. In many ways, Trader Joe’s is the anti-grocery store. The parent Aldi banner operates on a very similar business plan, just with a different price and value message. In both cases, the use of strong architectural and graphic elements along with innovative signage is creating a different center store (and total store) experience. So is the retailer’s use of own label to offer upscale product offerings to shoppers at discount prices.

The challenge is clear but immense: retailers need to move rapidly to optimize the store for a shopper who is now capable of creating his or her own expertise digitally—highly informed and individualized in behavior. This creates a set of demands on the store, ranging from employee capabilities to company requirements, as business transforms to become truly omnichannel.

The Building Blocks to the Future Shopper

Understanding the Future Shopper: Key Insights

The shopper and the store in a decade’s time will be shaped by the changes already underway today. But to establish how that future will interact requires moving to a stronger framework of common requirements. The key elements to guide how to build this mutual space can be summarized in the following future-focused insights model⁴:

Connections

Flow

Simplicity

Experiences

4 The Connections, Flow, Simplicity, and Experiences model appears courtesy of Kantar Consulting’s Futures Group.

Connections

Virtual, robotic, and augmented pets all are available today. In the future, they will become the shopper’s assistant—aiding in searches, interactions, and connecting to media and multiple-mode communications. The retailer should anticipate accommodating and enabling these ‘assistants’ when engaging with future shoppers.

Sources: Virtual Trends, Sony Corp, and The Imaginative Universal

Shopper needs are also evolving to enable more quality time with friends and family, deeper relationships with service providers, and community connections—mostly all of these needs are working “against” the isolating pressures of modern, hectic lifestyles. These emotionally oriented needs will continue to evolve as the digital world penetrates deeper into the every day. Relationships between individuals and their larger communities are under strain, with time increasingly dedicated to social media and apps that help foster interpersonal relationships. Moving forward, the virtual and physical will blur further as access to digital moves beyond computer interfaces and smart devices—virtual and augmented reality will be layering one on top of the other. For example, many shoppers will have a virtual pet via AI that only they can see; still others will be granted permission to shift electronic devices to augmented reality. It will be the roving interface of the shopper, shifting from real to virtual locations as the AI and shopper converse, even walking through a physical store.

In this new technology-rich world, retailers will need a great deal more expertise to understand the hybrid world of overlapping realities, learning how to insert themselves in relevant and appropriate ways—largely defined by the shopper and his or her digital assistant. Those retailers who insist on interruption rather than integration will be systematically removed from the decision set of the shopper. Greater opportunities for retailers will also emerge from radical changes to the catchment areas of physical stores—defined less by proximity, traffic, or geography, and more by crossing physical channels with virtual borders. Building and maintaining appropriate connections with shoppers will require seamless transactions and fulfillment, as well as integration into a larger web of day-to-day shopper interconnections.

Flow

“Flow” is a requirement that is raised in large part by a shopper’s increasingly complex life enabled by seamless connections. Pressures include time compression, the collapsing of work and personal time, demands for greater efficiency and flexibility, as well as accessibility of relevant products, services, and spaces. In part, this means coping with the new “normal”—i.e., constant change—by establishing an integrated view of how to integrate and sequence everything from meal planning to product prep and consumption. The risk for retailers is to have stressed, overwhelmed shoppers withdraw. So success in the future will require some controls and appropriate intelligence to help loyal shoppers manage the overall “flow,” making life work better.

Managing flow will optimize automated services like home (or workplace) delivery. Similar to a factory constantly improving just-in-time (JIT) processes, the home will review and improve on how to ensure that product and service need matches moment of use. For the retailer, this demand will require assessment of each shopper’s changing needs and purchasing patterns. Retailers who can become an integral part of the shopper’s lifestyle will maintain competitive advantage.

Optimizing “flow” requires intelligent sequencing of decisions and events to handle future complexity, basically making life work better for the shopper.

Simplicity

Shoppers in the future will continue to seek ways to minimize the growing complexity of modern life, making decisions less taxing and finding solutions that can anticipate needs rather than respond to them. Product curation is often suggested as a solution, but retailers will need to master far more than individual preferences and product matching. As noted earlier, life will be managed within the complications of layers of reality—aided by digital assistants, AI, and virtual reality. Thus, human decision-making will ebb and flow. Simplicity will thus be achieved by effectively managing all of these nuances.

Identifying low awareness with repetitive need purchases (via monitoring usage and need) will help automate a purchase, aided by flow management. Many products and services will thus shift to a direct-to-consumer (D2C) model, entirely bypassing the retailer. For higher-level awareness situations, such as a birthday or return from vacation, the retailer will offer up the right set of product selections. For product trialing or new experiences, some shoppers will select a specific retailer due to that retailer’s “own label” expertise, further simplifying the shopper’s life—as the retailer will make relevant selections.

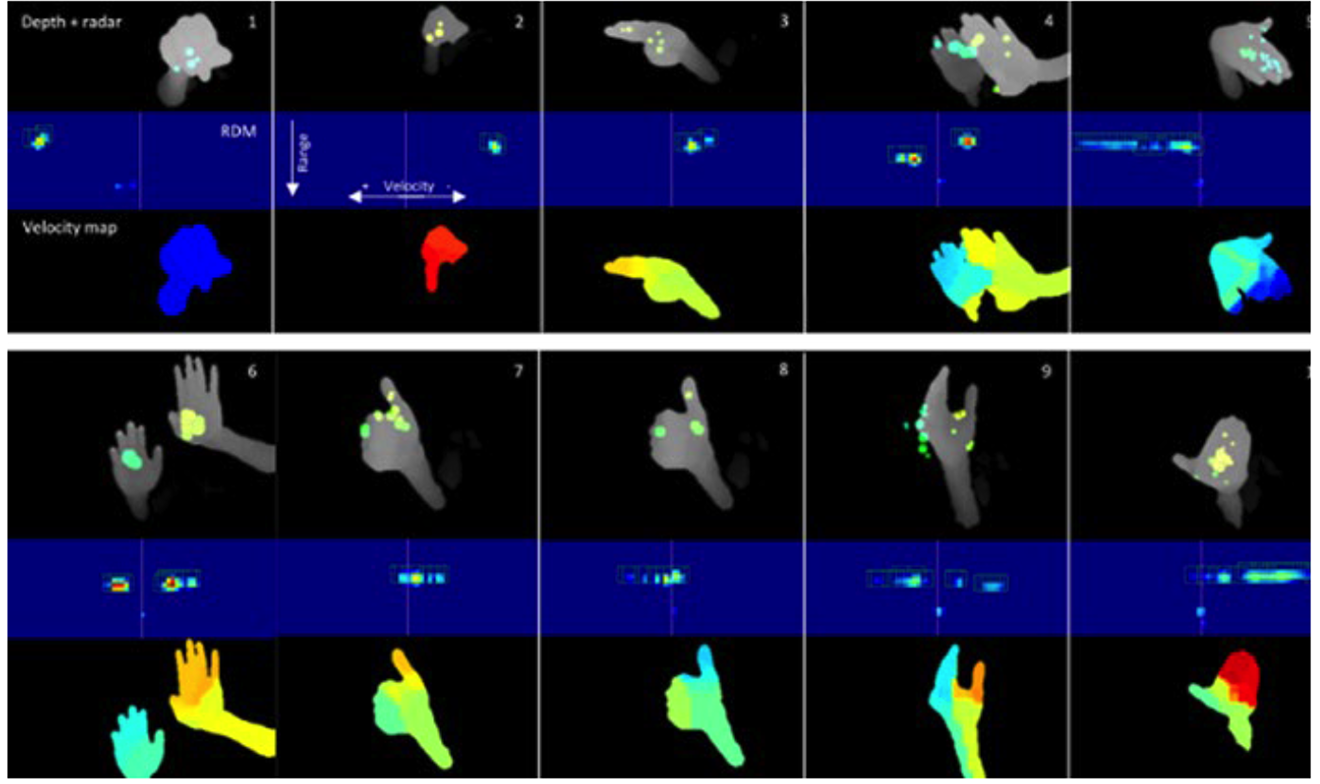

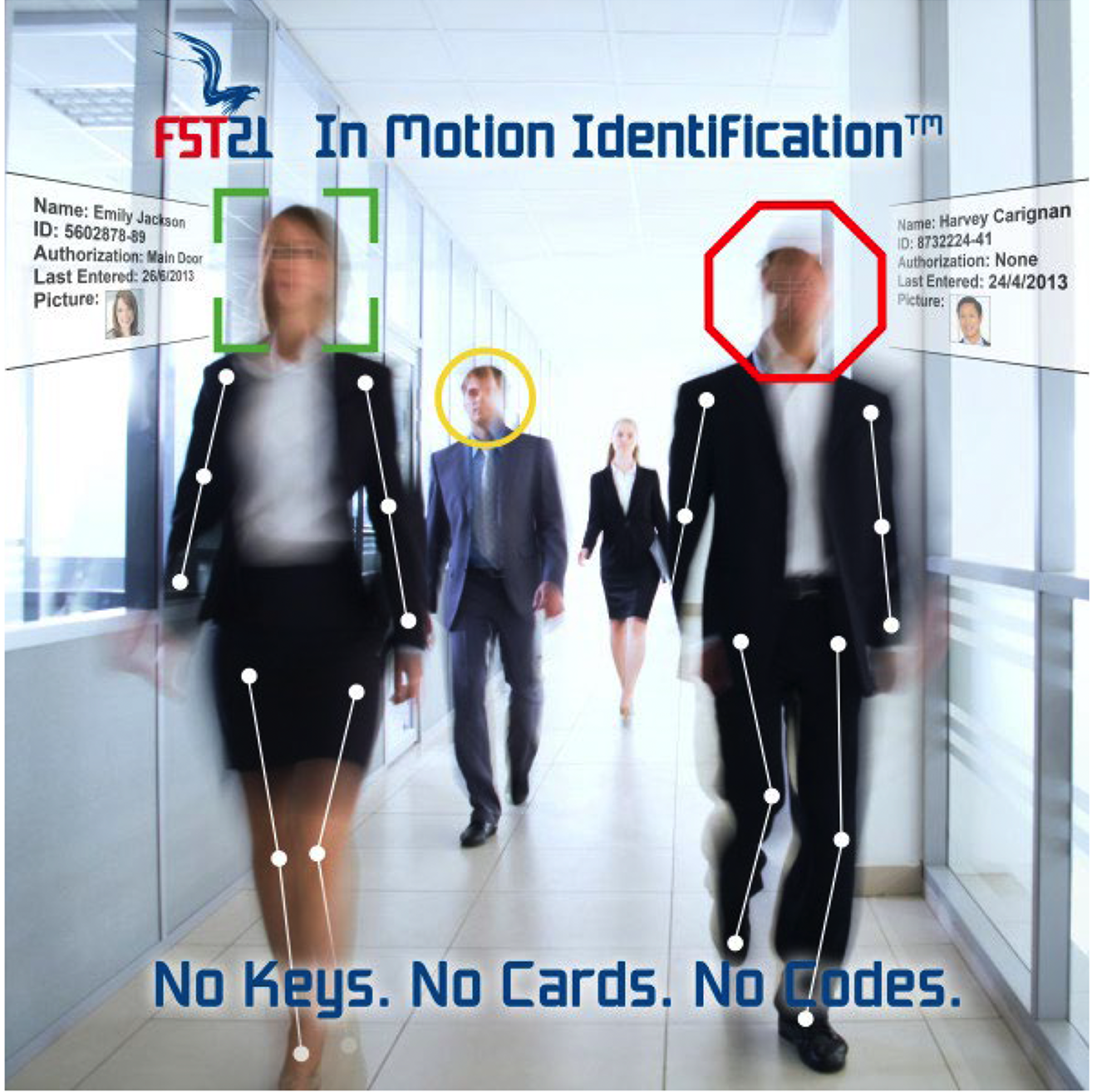

Identification via individuals’ unique gestures and body movements is already in use with areas requiring strict verification for access. The top graphic is a hand movement analysis that tracks movement through time and space to establish a unique pattern. At bottom, FST21 runs a visual evaluation of 12 points of the body moving toward a camera. The result for the retailer and shopper is a simplified identification process.

Source: Manomotion, FST21

Experiences

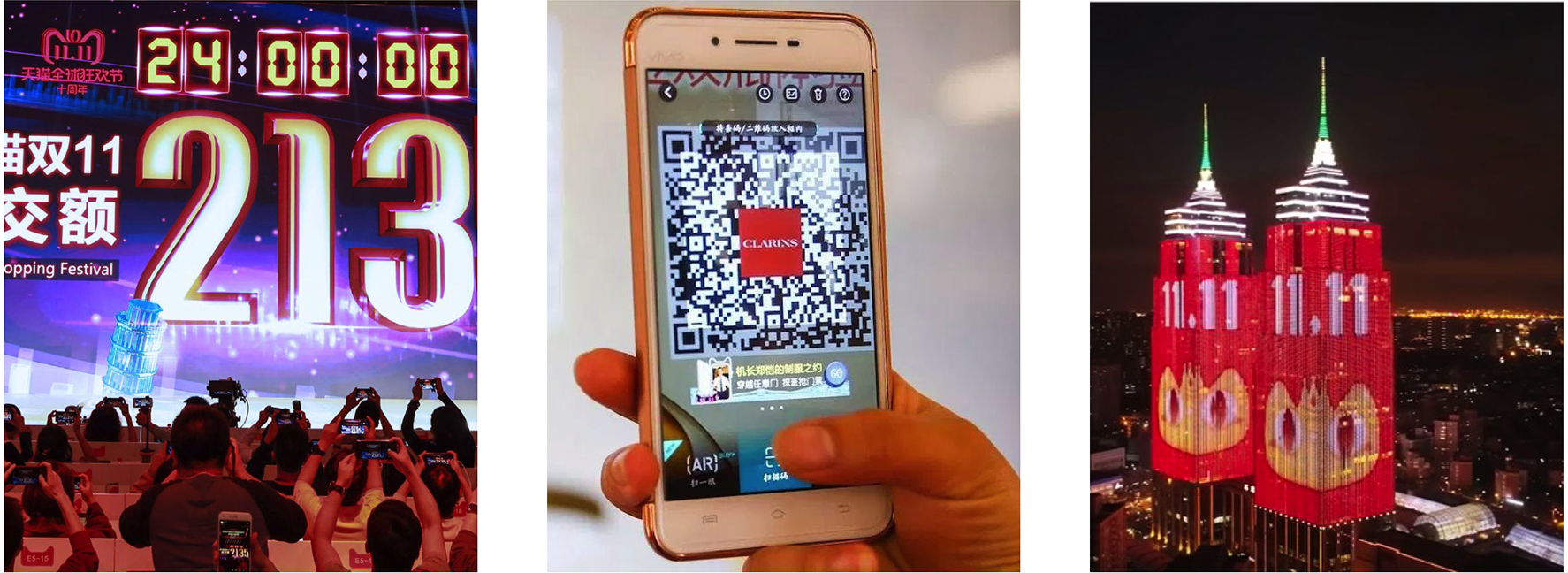

Alibaba’s approach to 11.11 “Singles Day” event continues to broaden into a wide range of integrated online, in-store, and in-mall events that are intended to keep the shopper engaged during the full event. From left to right, major events with group gaming and countdown clocks, smart device augmented apps from seeking and ‘capturing’ elusive branded characters to be redeemed for free goods, as well as major malls covered in clear LED panels streaming media and messages that can be seen across the whole of a city.

Source: Alizila.com

Today’s Epicurean shopper already expects the store to provide relevant content, curated products, and solutions to suit the experience. What was delightful and amazing last week becomes more routine, more of a background to the shopping experience. The same will be true in their lives as shoppers seek out new experiences stretching across multiple media, virtual reality, and transportation options. Note that experience is not always focused on delight. Public transit, for example, is now expected not only to be clean and on-time, but also efficient at communicating delays, offering updates anywhere the user may look — digital signage, smartphone apps, etc. Technology deployed in cars allows a car to take control from a human operator to avoid a mishap — while also suggesting optimal route guidance, food selections, and nearby entertainment options. Airlines prompt the traveler to change trip details based on rapid shifts in weather and aircraft availability. These changes rapidly become the norm for consumers. Similarly, retailers will generate content focusing on how to make today’s shopping enhancements fresh, new, and relevant to a shopper’s movement and specific place.

All of these shifting expectations will challenge retail planning. Eliminating the negatives will be the baseline for that assessment, and investment for monitoring store conditions, product availability, and employee positioning. But the positives will be harder to achieve since retailers are competing not only against each other but also with so many other touchpoints of individual shopper’s lives. Stores will rely on digital integration — for example, deploying media across whole walls that can stream media, change colors, and shift messages to individual shoppers'. Small sound zones will combine music and messaging to fit the mood, but not overwhelm or distract. Stores will constantly work to improve the environment to provide new, inspiring, and customized-to-the-shopper experiences.

The Components of Expertise

Core Tools for Future Expertise

Mobile Technology

Conventional retailers have been challenged by the availability of information provided by mobile devices and the smartphone. Mobile changes the way shoppers behave, with access to nearly limitless information on demand. Traditional mass-market advertising media continue to lose impact. Shoppers do still visit stores to educate themselves on products, browse merchandise, or find inspiration for their purchases. But, in parallel, they can access a staggering amount of useful knowledge in aisle, or even lose their focus completely. Employees often respond to a shopper query by running their own data searches independent of the internal support provided by retailer systems. This parallel activity will likely expand beyond the handheld; the open question is how that will function in shopper and store employee routines.

Payment management, banking, and transactions continue to expand into mobile, though in the US this is happening at slower rates than in Europe or Asia. The expectation is that like travelers transacting with airlines and hotels, shoppers will be forced into greater use of cashless payments. This is a change already occurring with smaller retailers and online players that have opened stores such as Amazon in the US where entry is denied to those not able to accomplish mobile transactions. Experimentation is now capturing gestures, voice, and facial recognition as a means of seamless transaction, some of which will likely surpass mobile technology over the next decade.

Once friction is removed from the payment experience, making it seamless to the received value, then price sensitivity is likely to be reduced.

There are clear benefits for retailers and shoppers: the shopper no longer must pause to pay while the retailer has greater security and less time in managing cash and checks. Another benefit will be a reduction in price sensitivity as the shopper no longer gives as much thought to the actual cost of the experience. Early evidence with ride-sharing applications shows this shift — the focus of the user is on ease and speed, much less on price. However, retailers must also contend with the fact that not all shoppers have access to credit and debit cards. Currently in the US, almost 25% of the population lacks a debit or credit card. How this translates into future retailing is of high interest but remains difficult to project — given variations such as lower income shoppers’ access to financial services, or broader fluctuations in discretionary spend during recessions or general budget-tightening trends.

At the same time, new opportunities are surfacing to leverage mobile technology. Geo-fencing, using GPS, RFID, or NFC can enable the store to interact with the shopper, triggering prompts, information, and in-store guidance. Done carefully, it allows the retailer to identify a shopper and drive appropriate messaging and responsiveness. Done poorly, it has risks of alienating shoppers who are already overloaded with marketing and leery of “Big Brother”-style privacy concerns.

A collection of cashier-less stores: top left is Amazon Go with a core mission of enabling shoppers to walk in (by scanning a smartphone with the app) and walk out with all purchases being recorded seamlessly. The upper right shows Bingo Box in China with a far smaller kiosk that allows the shopper to self-scan purchases which are visually verified on departure. The bottom photo shows a hybrid 7-Eleven in Taiwan with app scanning gates to allow the shopper into the store with the expectation of self-scanning.

Source: Kantar Consulting and Seven

Evolving Impact of Apps and Voice

Leveraging apps to aid the shopping experience is commonplace today. Apps integrate online shopping; provide in-store navigation; offer pricing guidance, reviews, blogs; and enable payment transactions and a multitude of fulfillment options. With a self-contained app, it can be easily updated and managed by the retailer (or third party) right on the shopper’s mobile device. Current challenges must be resolved prior to projecting this one-store retail solution to the future, not least of which is the stability and predictability of secure functions. In both instances a single failure usually results in the shopper stopping use of the app. Another risk involves overreach, i.e., piling on too many functions and behind-the-scenes tapping of data generation. An app that is constantly geo-locating and transmitting data (often not related to the retailer but for third party use) will slow the smart device and drain batteries. We expect that in the future, power issues will be resolved along with the need to manage multiple devices; nonetheless, retailers must focus first and foremost on the value the app can provide to the shopper.

Improvements in PCs, laptops, even automobile interfaces toward app-enablement has made this a perfect solution for retailers to provide “whole life” value, delivered across any platform the shopper uses going forward. And the ability of the app to sync with prior actions on all devices removes another form of friction and frustration for the shopper. However, in the future the requirement that the app be fail-safe expands considerably and will need to be reflected in long-term planning and system-wide risk mitigation.

Voice clearly opens greater potential for mobile technologies but future changes will make it far more so. Today, voice technology is still stuck in the ‘command and respond’ pattern modeled after call-center automation. The inclusion of chestnuts — i.e., somewhat random and neutral statements to indicate conversation — has helped, but at the core the function is still about making a request to be acted on. A true conversation capability is only now emerging in a few instances such as those associated with the Google cloud of solutions that include on-the-fly translation services. Ordering a product is a fairly direct though often frustrating voice activity. Merchandising and selling with voice requires a complete elimination of that frustration. That requires a natural give and take between the AI managing the conversation with the shopper to get to a positive outcome, even if only improving the shopper’s attitude toward using voice over time.

Voice will become far more effective once it can engage conversation with a recognizable personality.

For visual and audio interaction with shoppers and employees, the addition of a ‘personality’ to voice technology will optimize engagement levels. Interactive conversations providing tonality and emotional change are far more effective than the current flat and predictable sentences used by today’s voice-enabled devices. Standing in the meat department may generate a conversation with a TV chef’s voice discussing different options for dinner along with considerations for side courses. Or, shoppers will be able to engage a known brand spokesperson in the aisle. The interest of celebrities to license their voice reflects this reality, as does the interest of media companies to create new computer-generated voices. All of this technology today still requires a smart device. In the future, voice activation and engagement will involve various fixtures, localized sound cones, or other micro-focused discussion tools — enabling technology for most of this is already in use today. Avatars appearing on a flat surface or VR interface to provide visual cues to the conversation will also be deployed.

Voice as a means of two-way notifications and queries via an in-ear device will be common in the future. Speaking to a device has become a normal activity today; but newly evolving AI programs can finish sentences from spoken fragments — requiring fewer spoken words to convey meaning. A similar evolution has occurred with GPS-enabled mapping apps in which users rely almost entirely on the voice function to make changes to travel routes. In retail, we can expect the use of cues and alerts from store-centric AI functions. For example, a manager could be alerted via an earpiece or nearby vibrating surface to an impending failure in refrigeration, a lost child, an unresolved labor concern, or changes to a shopper’s product preferences.

Voice will become far more effective once it can engage conversation with a recognizable personality.

Logistics that Shrink Time and Space

Over the past few years, Amazon has set a standard for home delivery that most retailers are still unable to match, and those offering such services today are certainly struggling to do so profitably. Expectations have already shifted from two-day shipping to two-hour fulfillment in a growing number of major metro areas across the US. Evolving standards create greater pressure to compete: shoppers are no longer willing or required to make tradeoffs between fast, free, and convenient delivery.

Though the grocery industry has had functional models such as Peapod in place for quite some time, the shakeout of companies in the late 1990s such as Webvan, ShopLink, and others deterred most companies from investing and learning from these models. Now they are forced to make a choice between building infrastructure that enables efficient delivery or looking externally for ways (and partners) to fill the hole in these capabilities. Partnering with third-party and app-based delivery services is a quick answer for some but may not be sustainable in the long run. Third-party agreements also leave the retailer dependent on an external brand, and can disconnect the retailer from the shopper during fulfillment. Those looking to make changes organically must invest heavily to transform their legacy systems. To date, in-store pick-up has been the more cost-effective option for existing retailers and is increasingly favored by shoppers.

In-store pickup has the advantage of leveraging existing assets but is not without multiple challenges. As in-store pickup gains popularity, retailers are now looking for more ways to speed the process, move shoppers through the store faster, and ease the pain of return logistics. While digital sales grow, the role of the store is evolving as well, integral to addressing all of these related issues. Too often inventory at store level is not well integrated or suited to manage the volume, and the picking process is just as labor intensive for employees as it is for shoppers — while adding costs.

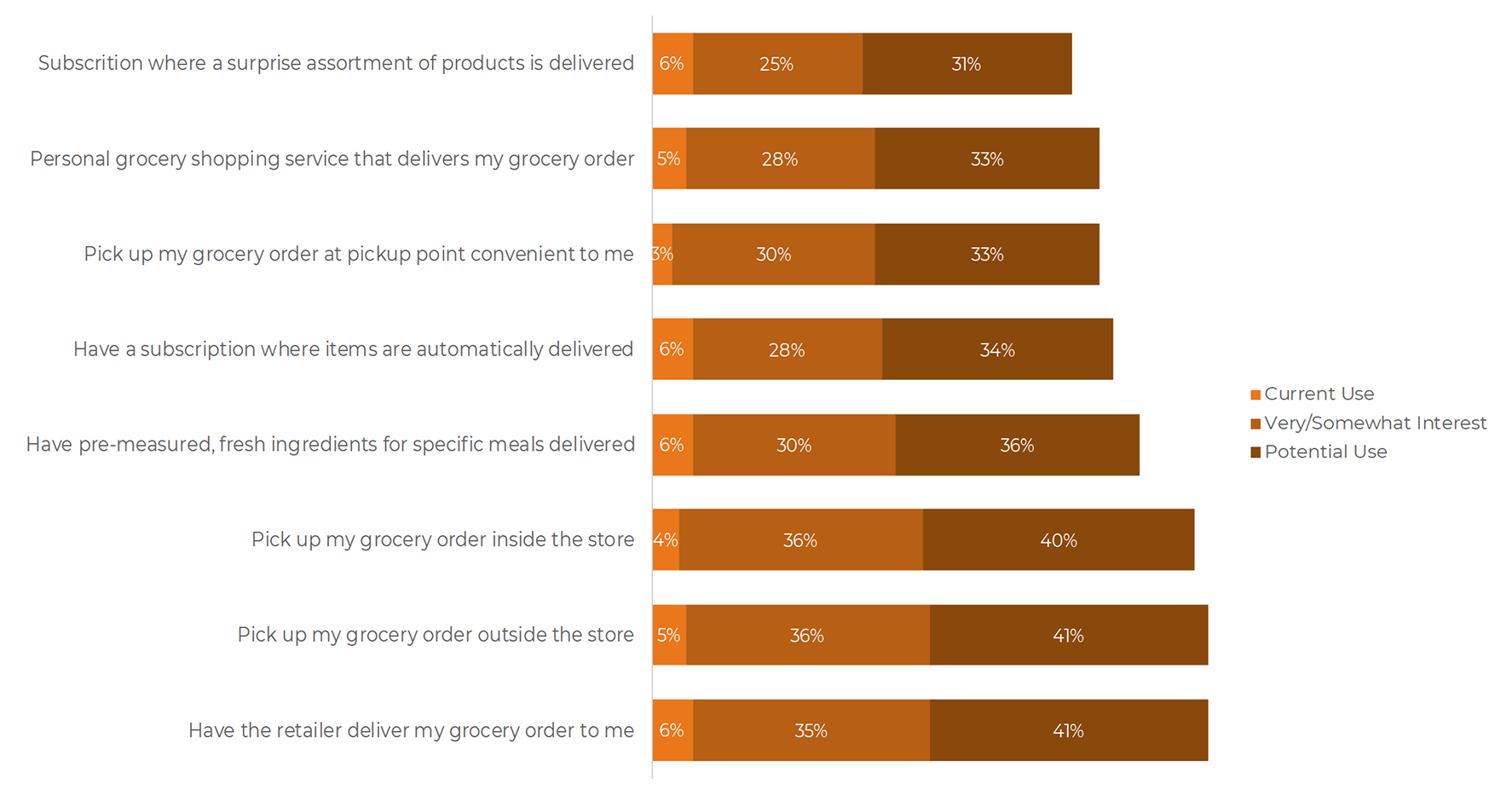

ShopperScape® data shows that shoppers identify key parts of the shopping trip that can be resolved with tools that reduce friction. Delivery and Pickup lead here. Source: Kantar Consulting and ShopperScape, February 2018.

Source: Kantar Consulting and ShopperScape, February 2018.

Kroger, the largest traditional supermarket chain in the US today, appears to be trying a bit of everything, making initial investments to assess what may have long-term viability. Such initiatives include Kroger Restock, Kroger Ship, Kroger Pickup, Instacart, an international agreement with Alibaba, an agreement with Ocado to develop improved systems, and — perhaps most interesting for the long term — the testing of a new self-delivering grocery service, combining robot technology from Nuro with Kroger’s grocery products, enabling goods to be curb-delivered via automated robots.

Kroger is clearly willing to devote resources to experimentation without absolute certainty of what the future outcome may be, a mindset that may be of more value than the specific programs being tested today.

Existing legacy systems will not suffice, if only because Amazon continues to raise the bar, and other retailers including Walmart are responding. Shopper expectations continue to evolve as well. The continued struggle is to reconcile in-store inventory draws for online orders without compromising automated replenishment systems. The future store will solve most of these issues with considerably more integration into shoppers’ homes and mobile lives, along with solutions for treating all inventory within the retailer as one object, extended outward into third-party distribution as part of a newer, larger pool of available product.

Regardless of the means of fulfillment — whether pick-up, delivery, third party, or spread across multiple routes to the shopper — the assets of the store will need to operate in parallel so that the system can fulfill any and all shopper requirements. Consolidation of orders from multiple suppliers into the home will be the standard within these stores. Achieving that standard will be easier with forecasting based on deep knowledge of individual shopper habits and needs over the longer term, either directly with the shopper or through advanced use of segmentation, leveraging an optimized range of shopper profiles.

Amazon clearly is an influencer and has been investing into logistic assets beyond leveraging existing services. These include seaboard and rail consolidation for cross-border fulfillment, dedicated transportation and delivery via air and ground vehicles, along with continued exploration of alternative placement of smaller fulfillment centers in population centers. In ten years, autonomous vehicles’ dependability and safety are likely to be resolved, expanding the portfolio of fulfillment options. In all of these areas, it is better for retailers to be fast-followers of proven solutions than to invest at levels requiring significant financial risk.

Warehousing and Distribution

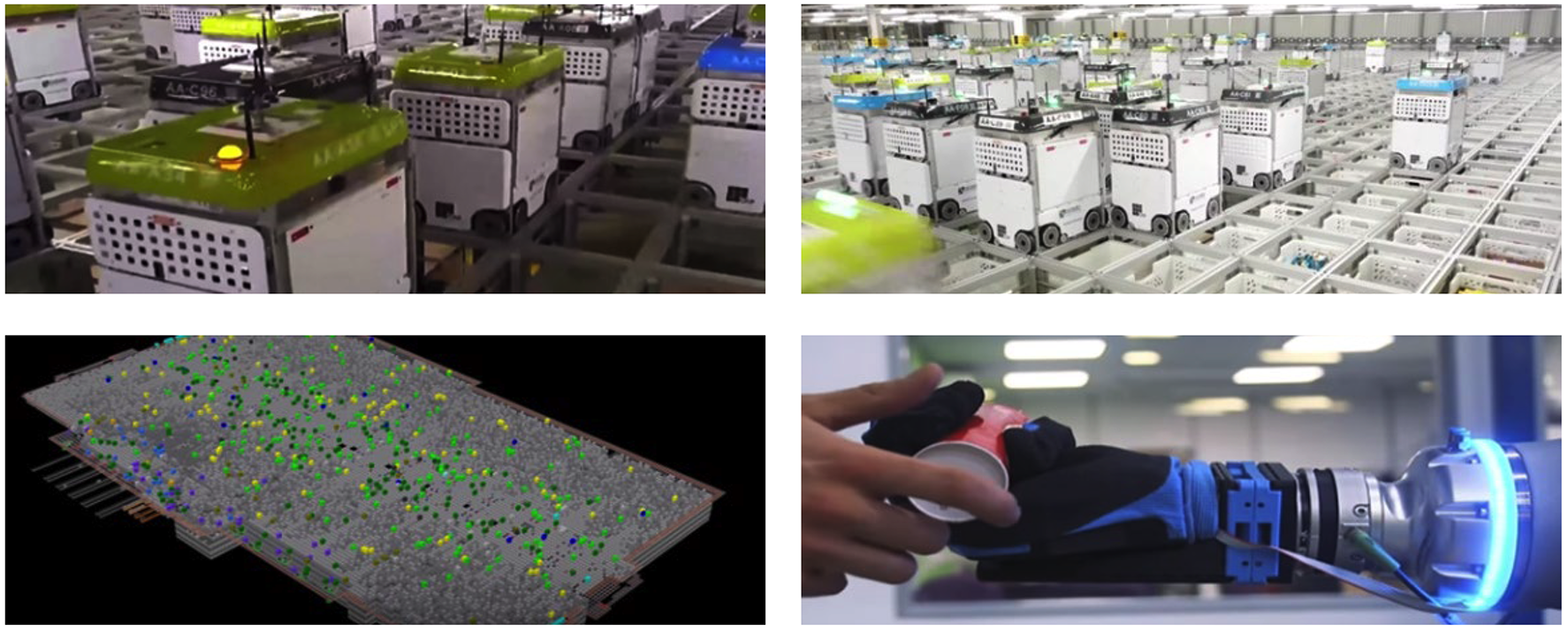

In Ocado’s newest distribution center (being built in the UK), all containers operate on a grid via bots. The bots collaborate to retrieve bins and deliver them to a station as quickly as possible. This allows an entire online grocery order to be picked in about 15 minutes (compared with two to three hours in previous DCs).

Source: Kantar Consulting, Ocado Investor Website

Technology and logistics capabilities will inevitably move farther upstream than the store itself. Several US grocery retailers are investing to build out online grocery supply chain capabilities. As noted earlier, Kroger is looking to British expert Ocado to help build out a first-party online grocery distribution center in the US. In the future, this new distribution model will enable Kroger to be far more in reach of its shoppers’ homes.

The warehouse of the future will be a heavily automated function for distributors and retailers that continue to replace traditional movement processes with in-place robotic arms and pallet shifters. Amazon’s Kiva has shown that relatively simple mechanical robots can be used to constantly optimize the motion and stationing of product within the warehouse. It also shows the ongoing development of human-robotic joint environments creating far greater productive models. This whole environment will be complex, but also data-rich — generating information to optimize the flow of assets. For example, the traffic lanes of goods to shopping may be slowed on a random basis by a robot moving a set of shelves to a worker at a critical moment, or the robot being replaced by an employee who can judge the timing better.

Warehouse and distribution will be part of a ‘whole’ that integrates the store and the shopper, and can anticipate the changing needs of each.

In the future, the store will have these capabilities and will become expert at handling not only product but also fixed merchandising and gondolas. Moving the breakfast convenience area to the front of the store based on prior demand and traffic history and changes outside of the store (weather, traffic) offer some simple illustrations. Shifting deliveries in mid-fulfillment based on data related to store conditions, employee activities, and shopper need sequencing becomes a normal part of operations. In short, the store of the future will be flexible, faster, and much smarter overall.

Automation and AI Create the Smart Space

Automation, when functioning as designed, is nearly invisible — but is neither simple nor linear in execution. The supply chain is a good example of how automation has become a complex series of actions that are recorded as transactions (the loading of a truck), signals (a message that the loading is done), and response (confirming the truck has left the warehouse). The greater the volume and quality of data being moved, the lower the costs incurred. Such a system also brings increased reliability of predictions, like being in-stock. Automation brings ongoing improvements, and the addition of AI means that the whole signal-and-response process now links to a range of additional variables.

In simple terms, AI describes leveraging the speed of computing to assess the statistical relationships in data. In business terms, AI describes a system that is actively assessing the relationships of disparate data sets to better understand results.

The above example of supply chain automation involving the loading truck expands with AI into a far richer approach to improving results. With AI, a truck arriving on time for a store delivery becomes a factor of the driver’s history, the condition of the truck, the manner it was loaded, variable traffic along driving routes, road conditions, weather changes, and legal requirements for distances traveled, including mandatory driver rest periods. It can also include the days the driver has been on the road, ongoing third-party disputes, and witnessing accidents along the route. Each of those variables has captured data that has a statistical impact on the desired outcome: an on-time and safe delivery. That data is also highly dynamic, changing over time and circumstance to which AI is constantly reevaluating and trying to expand into other relevant information that may help to further refine assessments. This activity is often stated as ‘machine learning’ in the trade press — and it does have some parallels to how humans process and learn from circumstances.

Enabled by smart technology and AI, the store of the future becomes an active rather than a passive operating environment.

In the future, AI will enable far faster rates for data gathering, access to broader data groups, and ever improving software to create scenarios based on relevant results. And, more often than not, that selection process will also be handled almost entirely by AI.

The Smart Store

The smart store will recognize the shopper at the entrance, or even better, outside the store using behavior movements signaling intent to enter the store. Recognition software for vehicles is already in place, and facial recognition is now hitting its stride with increasing reliability. It is perfectly feasible for the store to recognize repeat shoppers and link to their purchase history or preferences, to classify the type of trip they are on based on their movement and interaction with merchandise. The technology already exists to recognize a shopper’s emotional state via types of movement and expressions as they move through the store, leading to opportunities to expose the shopper to products of interest or head-off potential negative issues that might be arising, such as waiting too long for services, frustration due to not finding an item, or even searching for a lost child. The shopper’s experience can be personalized to some extent: for example, the embedded screen in the specialty cheese case “knows” he or she likes bold-tasting cheeses, the deli case “remembers” a preference for smoked turkey and might suggest another item with a strong affinity such as Swiss cheese, the floral department can issue a friendly reminder of important dates (tomorrow is your anniversary), and make recommendations to types of arrangements along with when and where to deliver at the optimal time during the day. And, of course, the store knows the shoppers’ financial information, assuring a pain-free and convenient checkout experience. There is already a practical record of success in upselling and extending service offers while in store, which is a natural extension of “smart store” interaction with shoppers. Three variables determine how this will work for the shopper and the store:

- Speed: Shopper-facing AI is less about novelty and more about convenience. AI should be employed when it can handle shopper issues faster or more reliably than feasible alternatives.

- Mobility: Consider how your customers will engage with AI and whether fixed in-store points of interaction can fulfill shopper needs or if mobile options such as robots or AI smartphone integration make sense.

- Integration: Make sure that AI systems have live access to the latest in-store data (e.g., inventory) as well as ensuring that employees can access AI conversations to smooth transitions from AI-to-human over to human-to-human engagement as needed.

The Smart Home

Samsung “Smart Home” takes advantage of the broad portfolio of home, computing, and media products that are now integration-enabled. The company sees the kitchen as the center of home activity and communication so has placed the primary point of engagement in the refrigerator. The interface can stream media, act as a touchscreen input, or be voice-enabled via Samsung’s “Bixby” AI app.

Source: Samsung

Today the Smart Home is an integration of a smartphone with several in-home devices. The doorbell is also a video monitor, the thermostat can be programmed, and music can be selected and played via the phone. This integration now syncs to voice commands on Amazon Alexa and Google Home, but in most instances home devices are managed via smartphone. What all these actions have in common is a 1:1 set of actions triggered by the user. Few if any of the in-home appliances or devices communicate or respond to each other though they often have some (limited) capability to do so.

The model that’s emerging focuses on protecting and serving those residing within the home. This requires linking all occupants to the surrounding monitoring and evaluation tools — enabling the system to act proactively and evolving from today’s “command and respond” model. First-mover companies working in this arena focus on home security, motion and sound detection, fire and gas alarms, heat sensors, and entry alerts. Integrating and using them as a single system requires a software solution; speed of improvement has become a competitive issue with most providers moving to independent cell and power systems. So it is the integrated home, not the smart device, that is managing appliances, lighting, climate controls, and media either on command or in reaction to members returning home, or lowering the heat when there are more people than normal in the house.

Clearly there will be legal guidelines and requirements to what shopper information will be considered private and not for access. In this instance it may be a store query to the bank as to the credit limits available as opposed to actual balances on-hand.

Retailers and manufacturers alike have recognized this opportunity. Many are studying how to enable the integrated home while managing the flow of requests and data resulting from it. Samsung, as mentioned earlier, has been steadily enhancing its devices to interact and communicate with each other focusing on the kitchen as the hub of at-home activity and live conversation. Thus, the system’s primary touchscreen is installed on the refrigerator door. In turn, Home Depot and Lowes have created variations of the “total home” integrated solution. Some believe the most useful aspect of in-home integration is remote monitoring of aging family members who lack a nearby helper; solutions can be provided by trusted “connected” stores, responding to prompts for grocery replenishment, medication or prescription refills, or repair services for home appliances or medical devices.

Enabling “aging in place” will be a strategic goal for connected retailers in the future.

For the retailer, enabling aging in place is highly desirable since a shopper can be active both in-store and online. But once aging shoppers move to assisted living and extended care facilities they effectively cease to spend in retail. Enabling the retiring Baby Boomer population to age in place will remain a key planning consideration for retail in general, and grocers in particular.

Philips “Caresensus” is one of the integrated home systems that are rapidly emerging to address the requirements for “aging in place” at home. The system includes a range of different monitoring devices that track patterns of activities and home status to ensure that the occupants are safe. It can contact family members via the AI-enabled interface to ask if they are having issues in the kitchen, check if they’ve forgotten to eat breakfast and go for a walk, or prompt a visit to the store to pick up a few groceries.

Source: Philips Home Electronics

The New Human & Robot Working Relationship

Deployment of AI, both in distribution and in store, will influence cost savings, increase process efficiency, and impact retailers’ labor models. On a financial level, AI can help balance capital expense over time (not unlike eCommerce today) to reduce labor and improve shopper response times. Unlike a warehouse, stores have the added complexity of unpredictable shopper activity and resulting safety concerns. The store of the future can begin to deploy AI and robot technology only after shopper interaction and safety concerns have been addressed.

The store of the future will feature a complex system in which automation, robotics, and humans will collaborate, each adding value to the store, the overall business, and the shopper’s experience.

Today robotic automation can handle repetitive (and boring) tasks such as inventory monitoring and reporting on-shelf or in aisle. With online grocery fulfillment, robots will quickly become better than humans at tasks such as product selection and order consolidation. In both instances, shopper and employee safety are paramount. The risk posed by a robot causing injury due to falling onto a shopper or bumping into a shopping cart will spur insurance companies to establish guidelines before robots can be deployed.

For the near term, robots are likely to be restricted to areas of the store where shoppers and robots cannot interact. This is both emotional (some shoppers may be uncomfortable with robots) and practical (robots cannot effectively navigate unpredicted shopper movements). This will change quickly, and within the next decade we will see mobile robots moving out of secured areas or backrooms and into the store floor occupied by shoppers.

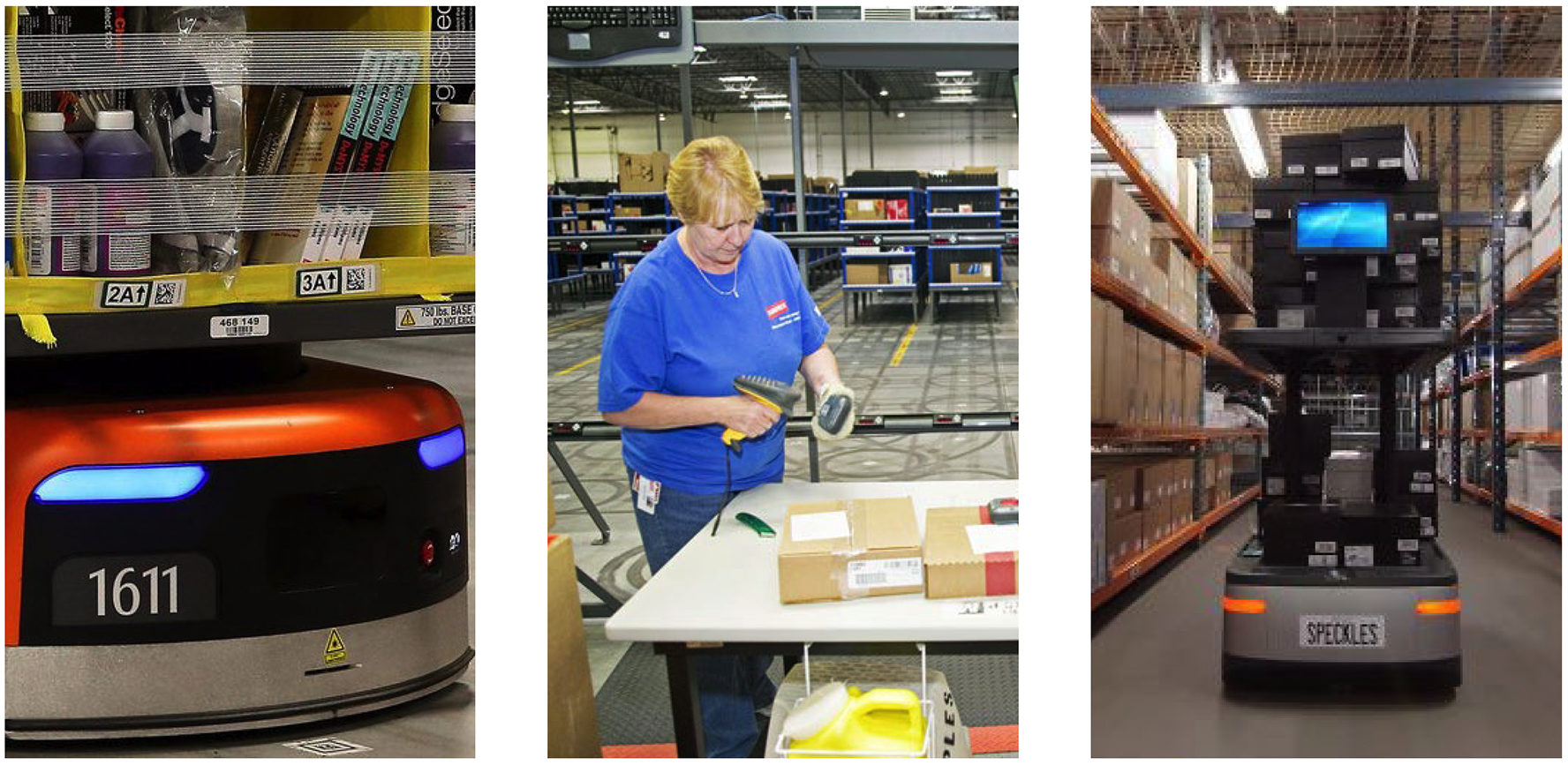

The strengths of the Amazon Robotics (Kiva) system include its flexibility of use that leads to innovations in product storage, integration with upgrades in warehouse software, and adapting to hybrid work environments that can continue to evolve with human interaction.

Source: Amazon

This is a logical response to some of the groundbreaking capabilities that Amazon began developing several years ago with its purchase and deployment of the Kiva robot system, now known as Amazon Robotics. Amazon purchased Kiva in 2012 and began deployment in 2014. The competitive advantage of this capability has less to do with the core technology and more from integration with warehouse and fulfillment software — the result enables a better model for humans and robots to work effectively in an automated environment. Amazon has made robotics part of its core fulfillment center strategies. In the coming decade, all competitive retailers will need to do the same.

Robotics development is a major investment for retailers, involving process redefinition, capital, and time. The returns are expected to be increased shopper satisfaction and shifting of costs from the P&L to the balance sheet.

New, ongoing labor costs will emerge as humans provide support for the robots themselves. Monitoring, maintenance, and updating will all be technical tasks performed in much the same way as the invention of the personal computer created needs for software programmers and IT support. Whether this will be at the store, district, or chain level — or outsourced entirely to a third party — is hard to predict, but at least some level of technical expertise will be required in the individual store. At the very least, store management will need trained staff to ensure proper robot operation and place calls for help as required.

Technology & Training

In a high-tech, omnichannel retailing world, talent development will be critical — on the front lines, where the work gets done. Meeting the requirements of associate and customer training will be critical to the store’s success in the future.